Have you ever been so frustrated by a problem, that you ran away to the mountains in obscurity for 5 years?

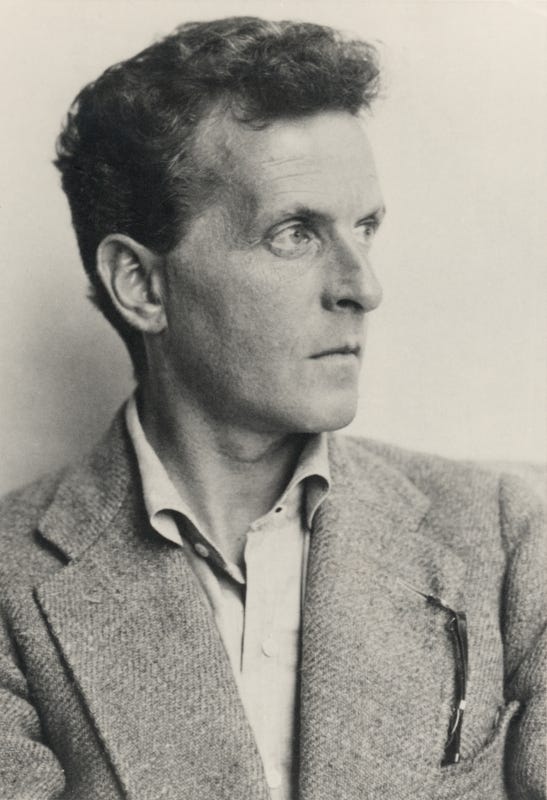

That’s the kind of response studying language can illicit. Ludwig Wittgenstein essentially gave up on philosophy after confronting his study of language and ran away to teach kindergarten. It’s so fundamental to our life that cracking open this subject can drive one mad.

But don’t worry, we’ll move slow and together. We’ve got this. Thankfully, Wittgenstein would come back to philosophy and many after him would continue his work, leaving us in a much better predicament to ask the question—what do you mean?

Thought

What can be said at all can be said clearly, and what we cannot talk about we must pass over in silence.

—Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

Application

Wittgenstein is potentially one of the most enigmatic characters of philosophical history. He emanates a certain passion for authenticity that so many others couldn’t even begin to fathom.

There are so many directions that we could go with Wittgenstein and with the study of language in general, but it might be most helpful to focus on one thought experiment of Wittgenstein’s later work to open our conversation for the week.

For a more detailed background of Wittgenstein as a person and the interesting direction of his professional life, check out the backstory below.

In his book Philosophical Investigations Wittgenstein is hoping to completely rebuild his work to that point. After years off from academia, he re-emerges deeply frustrated with himself and his previous approach to language

His frustrations all have to do with understanding meaning and use.

In this work he posits what would become his famous “Beetle In a Box” thought experiment. It goes something like this

Imagine a group of people are given a box that they, and they alone can see into. Each person describes what is in their box as a “beetle.” Each person claiming to have a beetle in their box, might hold a different mental representation or even understanding of what a beetle is. Even though each person claims to have a beetle, without being able to peer inside their box, it’s very possible that each person has something different, perhaps nothing at all.

Think of it this way, you can never see in someone else’s mind’s eye when they are recollecting for you an event, an image, or an experience you yourself cannot bear witness to. We are left to their representations to create another representation for us in our own mind.

This capacity is at once a defining characteristic of human evolution, but also a limiting factor.

More than anything, Wittgenstein wants us to understand that we are most often discussing representations and pictures of what we think we mean and what we think we understand.

His work exposes just how little we understand each other, and just how much we take for granted that we do.

I consider so much of the dualistic fighting that occurs in modern public discourse and wonder what would happen if we accepted that we largely do not understand each other, and slowed down to listen, learn, and work through a conversation long enough to genuinely absorb someone else’s meaning.

Wittgenstein holds that genuine understanding is possible, but only by using ideal language—that is language without any ambiguity or double meaning.

So today consider your speech—are you saying what you mean? The ability to slow down and craft an honest sentence in today’s rapid world of constant noise is both an art and a discipline.

Backstory

Wittgenstein was born to wealthy family in Vienna Austria at the turn of the 20th century. He was constantly exposed to floods of classical thought and eduction as well as the most modern science and literature.

He had competing passions working on early projects of aeronautics as well as mathematics and logic. In 1911 he was studying at Cambridge under Bertrand Russel (a famous philosopher in his own right) and was unsure of which discipline—aeronautics of philosophy—he should pursue.

He wrote a piece for Russel and asked him to evaluate it to tell him if he was “a complete idiot” or not. If he was, he would go fully into aeronautics, if he was not, he would delve totally into philosophy.

After reading the first sentence, Russel is reported to have said, “ No, you must not become an aeronaut.”

Wittgenstein began working on what would be his first major publication until 1914 when WWI broke out. Interestingly, he would finish this work—Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus—in a prisoner of war camp waiting for the war to end.

Even more interesting, after the war he published his manuscript, gave away his large inherited fortune to charity and to support artists, and disappeared for years in the Austrian Alps teaching kindergarten and working as a gardener at a monastery.

In this time of simplicity and introspection he came to realize that his work in Tractatus was completely wrong and misguided.

In 1929 he was invited to return to Cambridge where would remain as a lecturer until his death in 1953. While he published nothing else during his life (he remained uncertain after Tractatus if he could actually do real philosophy) he spent the remainder of his professional life writing and lecturing through his self-ascribed shortcomings and errors.

Much of this work was compiled and published after his death, including Philosophical Investigations which we referenced above.

Wittgenstein is unarguably difficult to understand, but I believe it is because he understands how flippant we can be when communicating. We’re satisfied so often in simply believing we understand other people, that we rarely do the work of clarifying our speech or that of others. The result is a world of people who mostly do not understand each other.

This is why Wittgenstein is quoted above in saying that beyond what we confidently communicate with precise language, we should not speak.

He was a proponent of ideal language which was a concept emerging in mathematics at the time that there existed a fundamental structure to all of language that was capable of communicating precise meaning.

Ideal language is a bit hard to understand, but in many ways this work would lead to computer code. Think of 1s and 0s which can only tell a machine to do one specific task depending on their arrangement.

Not having lived to see the advent of modern technology, he believed we should simply say what we can, and be silent about the rest.

I hope you found this short dive into language and Wittgenstein compelling, and I’m excited to see you tomorrow for an overview of Maria Montessori—one of the first women in Italy to a earn a PhD, and an incredible student of language and its application.

Until then,

TPP

References:

The Great Conversation, Norman Melchert (pp. 597-635)

https://virtualphilosopher.com/2006/09/wittgenstein_an.html

Image: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ludwig_Wittgenstein#/media/File:Ludwig_Wittgenstein.jpg